The study's approach

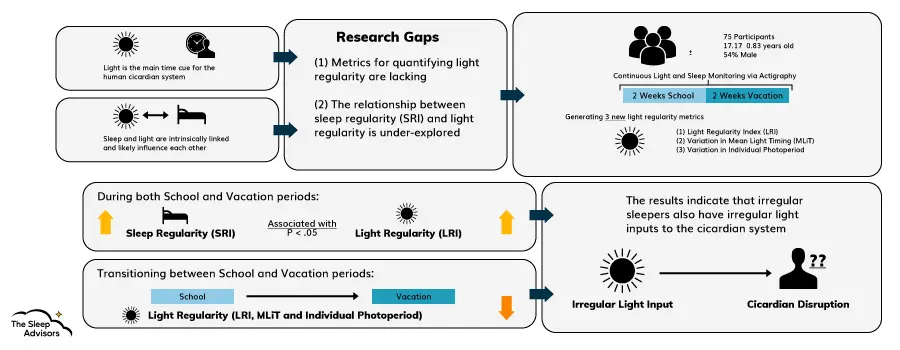

To investigate the intricate connection between light and sleep regularity, researchers in this study focused on 75 adolescents aged 15 to 18. Adolescents provided an interesting subject group because they often experience variable sleep patterns due to factors like a natural shift in preferred sleep timing and early school start times.

On top of that, adolescents have also been shown to be more sensitive to light (especially evening light exposure) at certain thresholds.

For this study, the participants' daily sleep and light patterns were monitored for a total of four consecutive weeks via Actiwatches on their non-dominant wrists. Two weeks corresponded to a typical school term, while the remaining two weeks represented a vacation period with fewer sleep constraints.

The researchers then compared the differences in light exposure to the changes in sleep regularity, if any were present. Both sleep and light exposure were also measured on multiple levels, dealing with duration, timing, and consistency.

We'll now go over the specific metrics used in the research, so as to better understand the variables at play and their relationship.

Measuring sleep and light regularity

To quantify sleep regularity, the researchers used a metric known as the Sleep Regularity Index (SRI).

This index gauges how consistent an individual's sleep patterns are.

A high SRI score (100/100) suggests a regular sleep schedule (they go to sleep and wake up at roughly the same time each day), while a low score (0/100) indicates irregular sleep patterns.

The study also took note of the sleep duration, bedtime, rise time, midsleep time and social jetlag.

Social jetlag in this context tried to account for the constrictions on sleep during the initial two weeks as opposed to the two weeks the participants were on vacation and thus unrestricted.

For light regularity, three novel metrics were introduced:

- Variation in Mean Daily Light Timing (MLiT): This metric focuses on the amount of time the participants were exposed to light above a certain threshold. This metric was also measured at different levels including both bright light and weaker light exposure (10, 20, 50, 100, 300, and 500 lux), as research does suggest that even light exposure of <30 lux can impact our circadian rhythm.

- Variation in Daily Photoperiod: This metric deals with the first and last time the participants are exposed to light at a certain threshold. Unlike the previous metric, this doesn't relate to the total amount of time spent above a threshold but rather just the first and last instance. This metric was also done for different levels of light exposure.

- Light Regularity Index (LRI): Similar to the Sleep Regularity Index, the LRI measures the consistency of one's exposure to light. This metric was essential for describing the relationship between light exposure regularity and sleep regularity.

The findings – the connection between light exposure and sleep

The research uncovered a compelling link between the regularity of one's sleep patterns and the consistency of their daily exposure to light. In simpler terms, individuals who maintained more regular sleep schedules tended to experience more predictable and stable daily patterns of light exposure.

And the researchers postulate that this is a two-sided correlation. So, people who are exposed to more consistent patterns of light exposure (have a higher LRI) are more likely to have a consistent sleep-wake cycle (SRI).

This conclusion was rather significant as not all the parameters of the study were as directly correlated. For one, a clear difference was seen between the first two and the last two weeks. Namely, sleep was both longer and started later in the day during the vacation period as opposed to the two “working” weeks. However, these facts were not reflected in the MLiT and Photoperiod measurements.

In other words, the consistency in light exposure seemed to be the driving factor when it came to the sleep-wake cycle. A high LRI also improved sleep duration and caused an earlier bedtime.

The impact of light exposure outside of the study

Now that we've established the premise and conclusion of the study, we'd like to talk in more detail about light exposure and how it can affect our circadian rhythms.

This is both so that we can use the findings of the study to help you make a healthier sleeping environment/routine, and to also point out a few facts that you might not get from the study.

For example, how artificial light comes into play (especially blue light), how it differs from natural light, and certain circadian rhythm sleep disorders that can be caused via light exposure, or lack thereof. Hopefully, by the end, you should have a clear picture of how light affects sleep and sleep quality and can make any needed amendments to your own sleep hygiene.

How sleep regularity affects your health

The reason we found the research into light exposure and sleep regularity so important is that it does come with real-life consequences. Aside from just general sleep quality and the feeling of grogginess commonly associated with sleep inertia, having an irregular sleep-wake cycle comes with more serious threats.

Namely, research suggests that an irregular sleep schedule is connected to several metabolic disorders, such as a higher risk for obesity, high cholesterol, hypertension, and high blood sugar, among other similar disorders.

On top of that, these conditions can in turn worsen your sleep quality. For example, diabetes has been observed to have a negative effect on your sleep while also increasing the odds of some sleep disorders like Obstructive sleep apnea.

This can then create a vicious cycle with negative effects on both one's overall health and sleep quality. The initial study specifically points to non-day shift workers as susceptible to these kinds of issues due to the nature of their occupation.

How light affects the sleep-wake cycle

While we've already covered how important the timing of light exposure is for our sleep-wake cycle, we'd like to dive a bit deeper into how light affects our bodies in general.

The fact of the matter is that this topic has been studied since at least the 1970s, with pretty consistent results.

Namely, our circadian rhythms, in this study called circadian pacemakers, are just short of a 24-hour cycle.

This means that to make up the difference, our pacemakers need some type of cue. And, interestingly enough, it also leads to our pacemakers being very adjustable.

Over the years, scientists have found that the impact of light is most noticeable during one's biological morning and biological night.

In other words, when you naturally wake up and are about to go to sleep. And we put emphasis on the phrasing “biological day” and “biological night”, as one's pacemaker can be altered drastically.

Notably, when exposed to natural light (or artificial light above a certain threshold), during the evening, your circadian rhythm can be “pushed forward” by up to two hours per day. And, if this process is then repeated during the following few days, one's biological night can be completely separate from actual daylight (if done in a controlled environment).

And this can then lead to certain circadian rhythm sleep disorders, such as delayed sleep-wake phase disorder.

The study even notes that these shift changes were observed in some visually impaired participants. So, it's not necessarily the visual component of light that leads to these changes but rather how certain receptors in our eyes react to light.

How artificial light affects our circadian rhythms

So far, we've focused on light as a broad concept. However, for the modern person, blue light exposure is arguably the most important when it comes to having a healthy sleep-wake cycle. And this is due to two facts.

Firstly, unlike in the wild, where humans typically experience very bright light in the morning (>300 lux) and then very dim light in the evening (<30 lux), the modern person is constantly subjected to medium levels of light (30-300 lux).

So, unlike wild animals that get a boost of energy and alertness in the morning and then consistent melatonin secretion towards the evening, humans are getting constant light exposure at different levels.

Secondly, a big part of the light we're exposed to is blue light, which has the highest impact on our circadian rhythms.

This is especially important given how prevalent nighttime indoor light exposure is from phones, computers, and other similar devices.

In other words, the light emitted from most modern devices has a very big impact on our sleep-wake cycle. And given that for many this type of nighttime light exposure is very common, our systems can find it more difficult to fall asleep and maintain a consistent schedule.

How artificial light affects mental health

While not an entirely separate phenomenon from what we've already described so far, it's important to note that the effects of light (short wavelength light or blue light specifically) also relate to our mental health.

For example, a study in the UK found that bright light exposure during the day reduced depression risk by 20%! However, this also works in the opposite direction. In other words, blue light exposure during the night has been linked with anxiety, stress, PTSD, and bipolar disorder.

As we've established, this is because blue light can suppress melatonin and make us feel more alert when we should be winding down and going to sleep. And while being constantly alert might help some prey animals, it's not conducive to good mental health. So, try not to have all of your wall lights at full blast during the evening.

How to use light to your advantage

Lastly, we'd like to take everything we've discussed so far and formulate advice on how you can better your sleep hygiene by controlling light exposure. Do note, this is not an alternative to sleep medicine and it shouldn't be taken as such.

In fact, studies indicate that combining these methods with sleep medicine is the most effective when it comes to treating Seasonal Defective Disorder (or winter fatigue), which is closely tied to your circadian rhythm.

In other words, these are just healthy habits and ideas for setting up lights in your bedroom that are the most sleep-friendly.

Bright light therapy

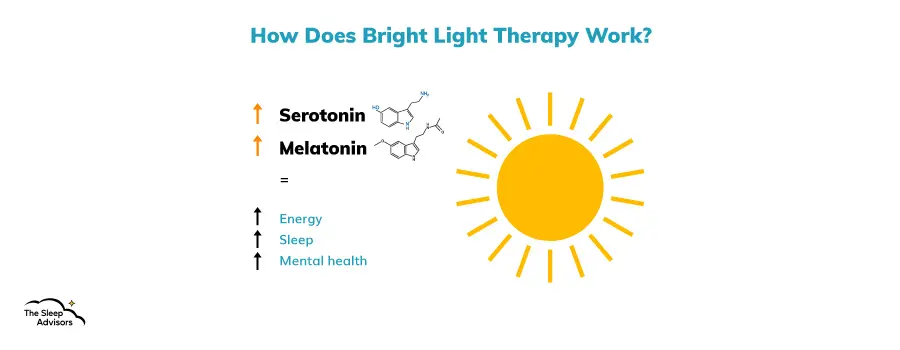

The first thing we'd like to focus on is bright light therapy, as it's a well-studied approach that has shown results when dealing with things such as SAD.

And, as we've mentioned, SAD is tightly connected to everything we've been talking about as it's a result of lower levels of light exposure and a disbalance of one's circadian rhythm.

The therapy itself is rather simple. It consists of using bright lights, typically over 10,000 lux (sometimes referred to as SAD lamps), and pointing the light at an angle at your eyes.

This is done first thing in the morning for about 30 minutes and relies on our body's response to bright light.

In other words, it sends a “clear signal” to the body that it should be alert, resulting in less grogginess.

Plus, when done consistently, it can help to form a morning routine, which we'll now talk about.

Forming a routine

A healthy circadian rhythm is essential for maintaining good health, both physical and mental, as well as a high sleep quality. And as we've established via the initial study, the human body wants consistency and routine.

Therefore, we believe that creating a morning routine that takes advantage of everything we've gone over can help many people “tune” their circadian rhythms. And here are the guidelines we'd recommend.

- Go outside early – Natural light exposure will wake you up and physical activity will also help tone down sleep inertia. Plus, during the winter season, you can only get natural light exposure during the day.

- Wake up and go to bed at the same time every day – This is recognised as the main pillar of sleep hygiene by many. It will allow your circadian rhythm to stay on pace and it will be easier to wake up naturally.

- Stay away from screens in the evening – While this one might be the hardest to practice, as most people are in the habit of using their computers or phones at night, it's also the most impactful when it comes to your sleep health. Sleep and circadian disorders can be triggered via nighttime blue light exposure and it's important to prevent that from happening.

Exactly how you decide to go about practising these tips is up to you. Some have found that blue light-blocking glasses help them fall asleep. Others might use dimmer lights and read a book in the evening for the same effect.

And there are even more involved procedures. For example, lights that imitate natural light and are set up to be more or less intense during certain times of the day. However, it was difficult to find concrete evidence of this kind of system producing results. Therefore, simple daytime light exposures and a solid routine would be our advice.

Keeping your room dark

Just as you can use light to wake up feeling more refreshed, you can also work on blocking it out to create a more calming bedroom. After all, as we've established already, your circadian rhythm needs an absence of light just as much as it needs bright, natural light.

Many people have benefited from sleeping masks in this department. And since they're rather cheap and easy to find, this is one of the easier methods of keeping your bedroom sleep-friendly.

Some people might also want to look into buying or even making blackout blinds for the same reason. This approach is equally as simple and effective as the previous one. Plus, you could always combine the two to ensure that no light manages to hit your eyes during the evening.

However, do make sure to draw those curtains back in the morning so that you don't feel groggy for the first half of the day.

Final notes

Can light affect sleep? We'd say that it not only affects it but is among the most important factors when it comes to sleep efficiency and a good sleep-wake cycle. In particular, a consistent pattern of light exposure seems to be directly tied to a consistent pattern of sleep.

Therefore, those suffering from poor sleep quality or irregular patterns could perhaps use the effects of light to their advantage. However, we will also mention that this does vary from person to person. Some people are more or less sensitive to light and therefore might experience stronger or weaker reactions.

Furthermore, we strongly advise that you read the original study this article is based upon. While we've done our best to condense the information we found relevant, many details were left out.

Spread the word

"*" indicates required fields

I've always found blackout blinds to be useful to help regulate my light intake